Every year, India announces its Union Budget on 1st February. However, this year, with elections scheduled for April-May 2024, the government has presented an interim budget instead of a full budget.

The interim budget serves as a temporary stop-gap arrangement covering government expenses until the new administration takes charge, typically for around four months. It focuses primarily on maintaining essential spending on ongoing schemes and critical public services. While minor changes in existing schemes may be announced, major policy pronouncements and significant spending announcements are usually avoided.

The full budget will likely be released mid-year and will be subsequently covered in a detailed brief by the Keshav Desiraju India Mental Health Observatory.

In the meantime, this blog will cover key components from the interim budget on the Union Budget for mental health.

The Union Budget for mental health consists of direct allocations under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) and some indirect allocations under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MoSJE).

For the current financial year (FY 2024-25), the health budget has amounted to around 2% of the total budget and the mental health budget is approximately 1% of the total health budget, similar to the previous financial year.

Mental health allocations under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

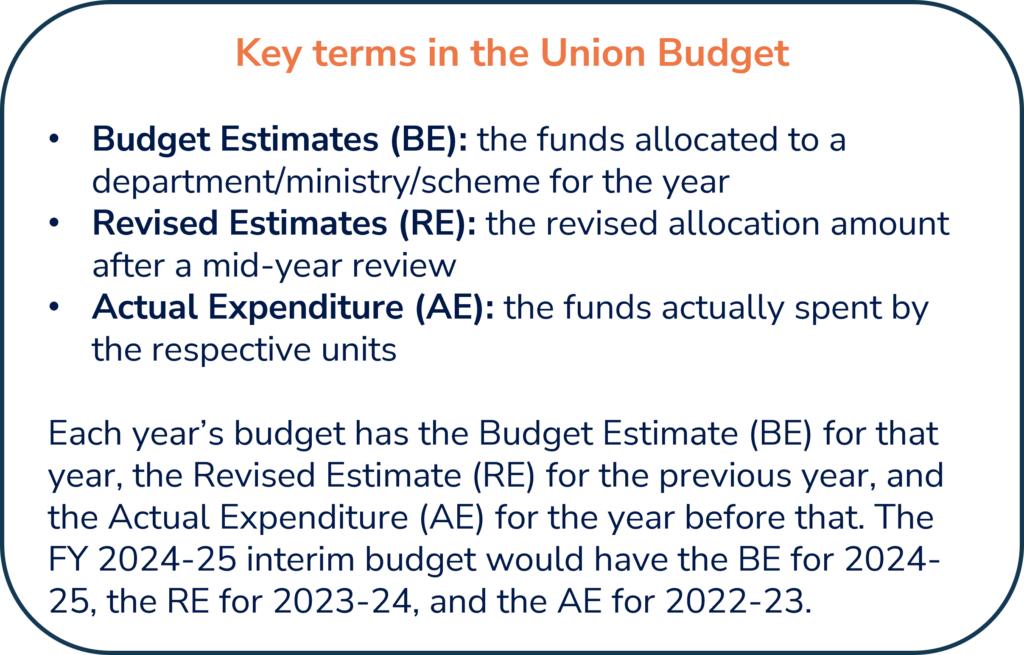

Over the last couple of years, there have been three main line items for mental health under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. These are allocations to the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro-Sciences (NIMHANS), Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi Regional Institute of Mental Health in Tezpur, and the National Tele Mental Health Programme (Tele MANAS). The following table details the line items as well as their allocation.

Allocations to centrally funded mental health institutions

NIMHANS has consistently received the largest allocation of the mental health budget over last few years, and this trend has continued into the current fiscal year. Notably, the allocation to NIMHANS increased 18% over last year. In contrast, the allocation for Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi Regional Institute of Mental Health in Tezpur, Assam was down 6.25% from INR 64 crore in FY 2023-24 to INR 60 crore for FY 2024-25.

National Tele Mental Health Programme (Tele MANAS)

Launched in October 2022 by the MoHFW, Tele MANAS was envisioned as a groundbreaking initiative aimed at bridging the gap in mental healthcare access across the nation. This 24/7, toll-free service offers free tele-counselling and mental health assistance to all citizens, particularly those in remote or underserved areas. Tele MANAS was heralded as a significant step towards improve mental health services offering vital support to those who might otherwise struggle to access such services.

However, the programme has faced challenges in utilising its allocated funds. With an allocated budget of INR 134 crore for FY 2023-24, the revised estimate for FY 2023-24 was only INR 65 crore, half of the allocated budget in FY 2023-24. The low utilisation for the programme raises questions particularly since the number of calls received have seen a steady increase according to the Tele MANAS dashboard indicating a clear demand for services.

Indirect allocations for mental health under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment

The mental health components under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment include allocations for Department of Empowerment for Persons with Disabilities. Within this, the National Welfare Program for Persons with Disabilities comprises of the Scheme for Implementation of the Persons with Disabilities Act, and the Deendayal Disabled Rehabilitation Scheme which encompasses of legal and rehabilitation support for people with psychosocial disabilities as well.

The overall allocation for the scheme has remained around the same as last year.

Reflections on the interim budget for mental health

For several years, the mental health budget in India has remained stagnant, hovering around 1% of the total health budget. A substantial part of this budget is allocated to one premier institute.

Budgets for mental health are pervaded by consistently low utilisations perpetuating a cycle of low allocations. This trend has been observed in funding for the District Mental Health Programme, discussed in detail in this issue brief. Given the burden of mental health conditions and the treatment gap in India, there needs to be an improvement in allocations and subsequent financial monitoring of such allocations to ensure full utilisation of funds.

Since FY 2023-24, the government does not disclose the allocation to the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP). The NMHP plays a crucial role in making mental health support systems accessible to the general public. Currently, the budget for NMHP has been subsumed under the consolidated head Tertiary Care Programme.

This is concerning in two broad ways. The first is the limited funding to the NMHP. The entire Tertiary Care line-item has been allocated INR 371.55 crore, while NIMHANS and Lokpriya together have been allocated INR 910 crore. This centralising of mental health care to two institutes limits accessibility to health care in settings where it is required. When services are centralised, there is also limited opportunity for continuity of care in local settings, which is crucial for mental health conditions including rehabilitation services, day care facilities and housing provisions among others. The second is the lack of transparency regarding funds allocated to the NMHP, severely restricting the ability to monitor and improve the programme and its funding.

The emphasis placed by the government on digital mental health interventions, as evidenced by the significant allocation for Tele MANAS and its designation as a separate line item since FY 2023-24, is notable. However, there are concerns regarding data privacy, accessibility of such interventions to the population that might not be tech savvy and their limited efficacy when the mental health care system as a whole is underfunded and understaffed.

Further, in a recent announcement the KIRAN Mental Health Rehabilitation Helpline has been merged with Tele MANAS. The stated purpose was to optimize resources and enhance service quality. While this consolidation might prove economical, financial and human resources from the MoSJE to the MoHFW would have to be appropriately redistributed to ensure adequate support.

Another welcome addition to the budget would be financial allocations to the Mental Healthcare Act 2017 (MHCA 2017) and the National Suicide Prevention Policy (NSPS). While both the MHCA and NSPS have the potential to reform mental health and suicide prevention in the country, the lack of resources to back their implementation has meant that their operationalization has remained sluggish.

Finally, in addition to increased and more transparent funding for the critical aspects of mental healthcare such as the NMHP, mental health requires a holistic approach and should have support from the government in terms of opportunities towards seeking education, employment and healthcare.

Authored by Sayali Mahashur, a Research Associate at the Centre for Mental Health Law & Policy, Indian Law Society, Pune.