Cost of treatment studies offer insights into the financial implications of health conditions on payers, patients, and healthcare systems. They shed light on the economic impact of a health condition and help policymakers plan for quality healthcare. Further, analysing costs helps us understand the health system and efficiently allocate financial and human capital.

Why conduct the survey?

There are few in-depth studies on the cost of mental illness treatment in India. In our issue brief, Understanding Costs Associated with Mental Healthcare in India, we reviewed 6 studies on cost of treatment in India. Though limited in their scope, coverage, and representation of individuals with different mental health needs, the studies highlighted the ever-growing financial burden associated with paying for mental health services. However, the evidence is still limited, and we were unable to draw generalised conclusions on the “affordability” of mental healthcare in India.

It is important to note that such costs go beyond expenditure on mental health treatment and involve indirect costs, the most burdensome being the foregone income due to time spent in mental health care. Hence, from April to June 2023, we conducted a pilot survey in the city of Pune to understand the cost of treatment for mental illness for individuals accessing mental health care in the city. We aimed to gather data on direct and indirect costs to eventually conduct a larger multi-location study across India.

What did we do?

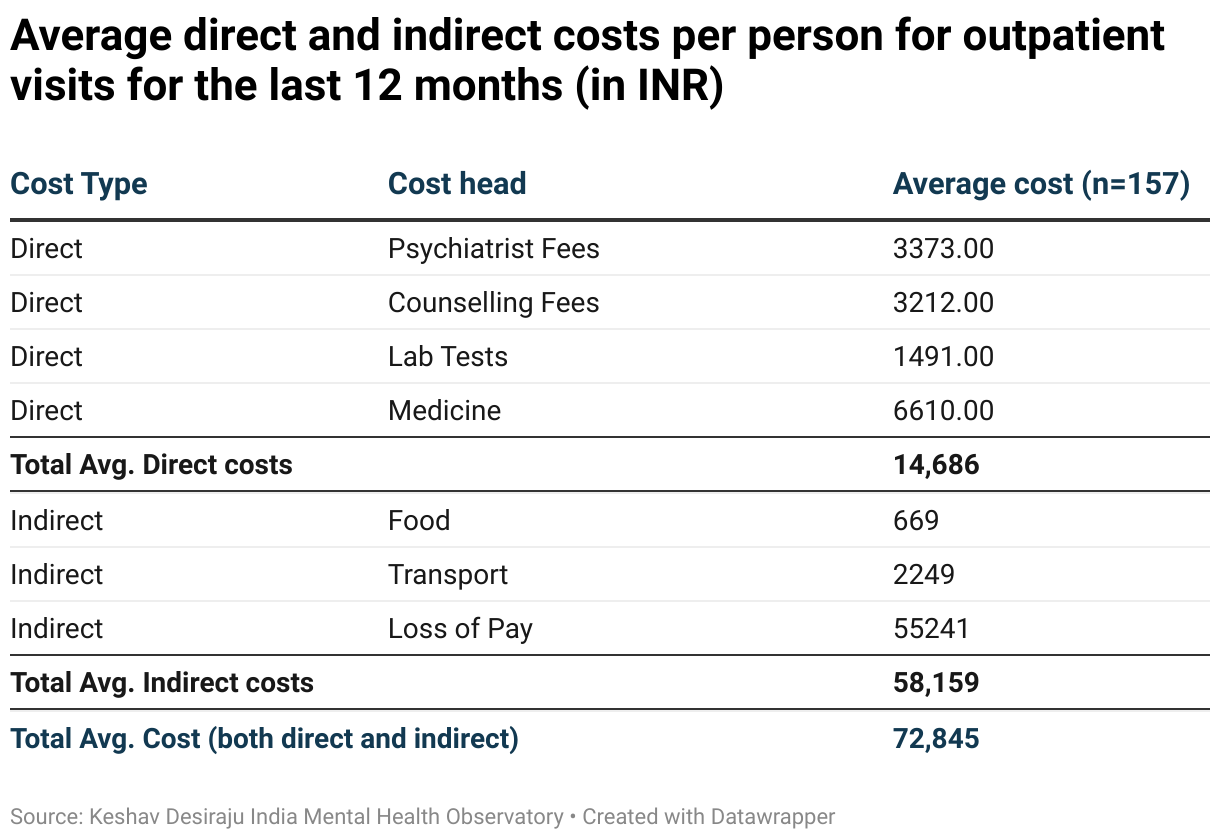

The objective of this survey was to determine the feasibility (can such a study be done?) and acceptability (is the study appropriate for the target group?) of implementing such a study. The survey questionnaire was designed by an interdisciplinary research team consisting of experts from psychiatry, financial services, public policy, and public health. The survey included questions on both the direct and indirect costs associated with mental healthcare and treatment that an individual would have borne in the preceding 12 months. Direct costs included professional fees, and costs of medicine and lab tests, and indirect costs included transportation, food, and loss of pay incurred by the service user as well as the caregiver at the time of treatment. We also collected information on socio-economic demographics, and details on mental health conditions and co-morbidities. To determine a suitable approach, we piloted the survey through in-person and online modes, with an initial target of collecting responses from 300 people with mental health conditions.

The offline survey was administered by an experienced data surveyor who received training on the survey questionnaire and data collection process. The surveyor approached around 10 private psychiatric clinics. These survey sites were chosen from organisational networks, considering the small sample size of the survey. While it would have been insightful to collect data from public hospitals, receiving official permissions was time-consuming. The data surveyor provided support by briefing each respondent on the purpose of the survey, receiving informed consent, filling out the responses, and providing clarification on each of the fields. On average, each survey took approximately 30-35 minutes to complete. All data was shared with the research team, anonymised, and stored according to data safety measures.

Parallelly, an online survey was shared through personal networks among psychiatrists in Pune and mental health self-help groups. Unfortunately, the online survey did not generate any responses. In hindsight, the reasons for this could be the length of the survey and the resultant respondent fatigue, support needed with the survey fields, etc. This is indicative that for such surveys, an in-person approach is appropriate considering the support and time required to fill out the survey.

What did we find?

Of the 165 participants approached, 157 responded after providing written information. The majority of respondents were male (65%), and over 50% were in the age group of 26 to 54 years.

From our sample, a large number of people, more than 50%, were either unemployed or retired. 50 respondents had dependents whom they were supporting financially. All costs were paid out of pocket as they were accessing private facilities; 40% of respondents paid for their own treatment, while for the remaining 60%, costs were incurred by family members. This shows the potential association between long-term chronic illness and financial dependence.

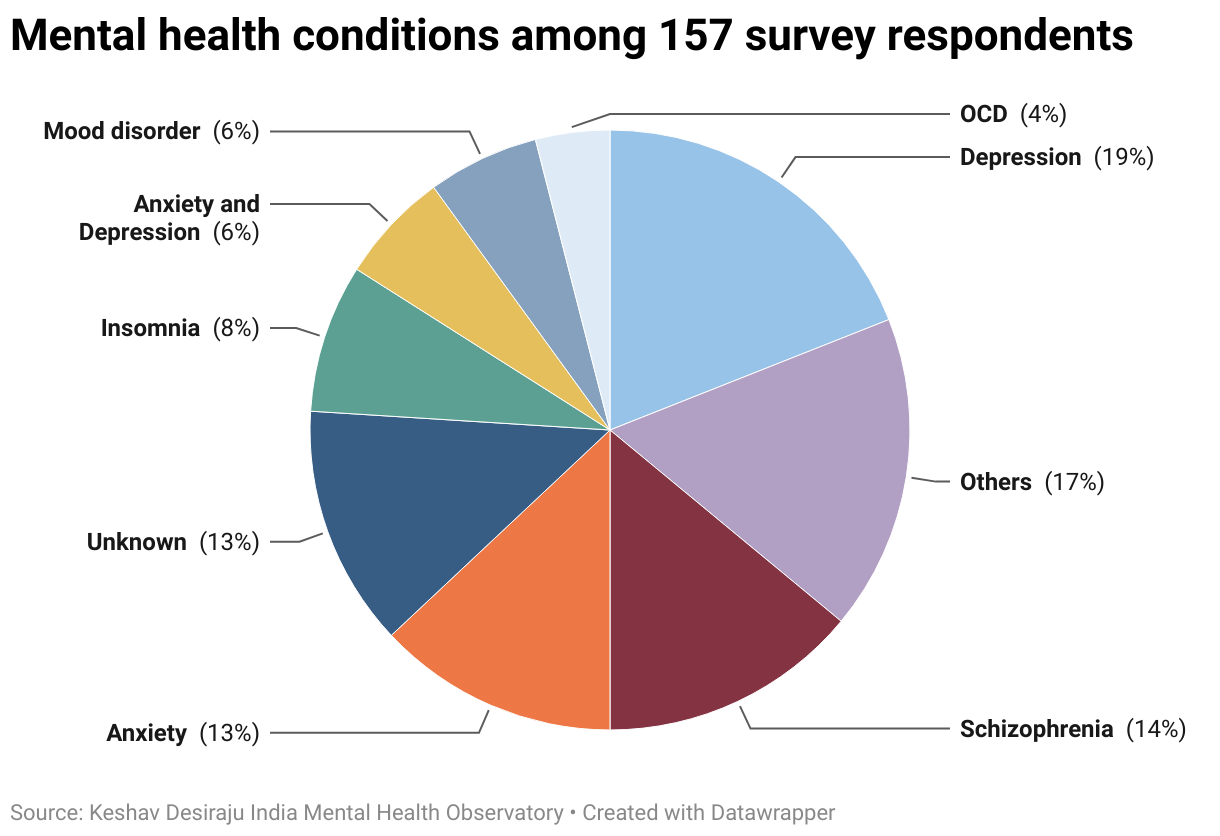

Among the respondents, the most common conditions reported were depression, schizophrenia, and anxiety. Out of the total respondents, 10 experienced hospitalisations in the preceding 12 months.

*Others include insomnia, personality disorder, postpartum depression, bipolar disorder, etc.

How much did the respondents have to pay?

The average cost for treatment of mental health conditions by individuals (both direct and indirect costs) amounted to around ₹ 72,845 for the year. Loss of pay, or the loss of income owing to unpaid time off or work unemployment due to the mental illness, including the treatment of the mental illness, was a major cost. Within direct costs, medication was the largest expense. Among those surveyed, there were 10 patients who experienced hospital admissions during the preceding 12 months. Individuals received inpatient treatment on multiple occasions. Hospitalisation expenses ranged from ₹ 15,400 to ₹ 4,31,500. These expenses were borne by either the patient themselves in 2 cases and by a family member in the remaining 8 cases.

However, even for a small sample, the direct and indirect costs of mental illness are considerable, as the per capita income in India is around ₹ 1,72,000.

Our learnings from this pilot study are that an in-person data collection approach by well-trained surveyors, fluent in the local language with the capability to provide adequate support to respondents, makes it possible to implement and scale such a study across multiple locations in India.

Going forward

We plan to scale up this study across other locations in India to generate data on the costs associated with treatment of mental illness, specifically the loss of income owing to treatment, and the significant component of out-patient costs that are not covered by insurance. We are also interested in knowing the differing choices, decisions, and trade-offs that people living with mental health conditions and their caregivers grapple with given rising health care costs and their socio-economic circumstances. The systematic data collection across cities will help understand the financial burden and impact of mental illness on persons living with mental health conditions and their caregivers. This data will serve as an evidence base for services and policy interventions to make mental health care accessible and affordable.

Authored by Sayali Mahashur, Research Associate at the Centre for Mental Health Law & Policy, Indian Law Society, Pune.