We understand now that there are links between suicide and social risk factors like poverty, exposure to domestic violence and abuse of alcohol.

[This blog post was first published as an article in The New Indian Express]

The alarming rise of suicides in India has not escaped national attention. Frenzied tabloids (reporting on celebrity suicides), regional newspapers and academic publications alike have tried to hold a mirror up to what is now a recognised public health crisis requiring a vast intersectoral response.

We know that suicide is the leading cause of death for young women in India, and India accounts for over a third of all female suicides globally. We hear about the burgeoning suicide rates amongst vulnerable groups such as farmers, students and the elderly. We understand now that there are strong associative links between suicide and social risk factors like poverty, exposure to domestic violence and abuse of alcohol. There is recognition that the loss of lives and livelihoods brought on by COVID-19 has deeply impacted the social fabric of the country, and it is not a far leap to assume that this contributed to the highest suicide rate in 2021 since NCRB began publishing this data in 1967.

In fact, the unmanageable pressures being placed on India’s institutional responses have led to the recent publication of a National Suicide Prevention Strategy by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in November 2022. Disconcertingly, though, what we do not often read, speak or hear about is the fact that the (soaring) rates of suicide in India are hugely underestimated. Let’s consider this systematically.

What are the reported rates of suicide in India?

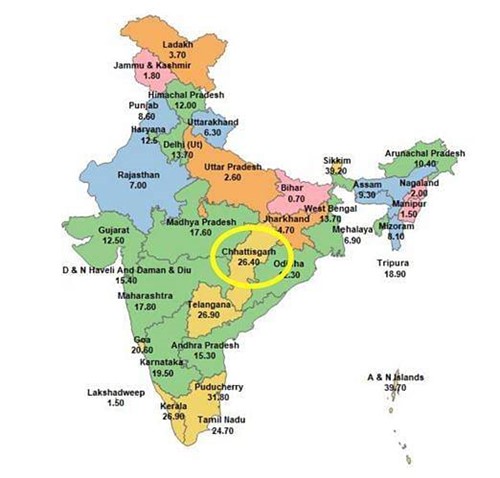

In terms of prevalence, official data reported by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) from 2021 estimated India's suicide rate to be 12, which means the country saw an average of 12 suicides per every 100,000 population (totalling approximately 1.65 lakh suicides in 2021). The reported rate varied greatly between states; from 39.2 in Sikkim to 0.7 in Bihar; although most states reported a rate higher than the national average of 12.

75% of those who died by suicide were men, and 66% of suicides occurred in younger people between 18 and 45 years old. The most commonly reported causes of suicide were family problems (33.2%) and 'illness' (18.6%), and daily wage earners consisted of 25% of individuals lost to suicide. 8% of all suicides were among students. More on these numbers here and here.

Although this data, as reported by the NCRB, does provide some insight into the particularities of suicide in India, these numbers alone only tell a small part of the story.

Where do we get these numbers from?

Despite the fact that attempting suicide is no longer punishable as a crime as per the Mental Healthcare Act (2017), suicide data is still collated by the National Crime Records Bureau in India. The reporting pathway for the NCRB is as follows: an unnatural death is typically reported to the local police, who will file an FIR and deem it a suicide after due investigation. Records of these FIRs are filed with the District Crime Records Bureau, which then collates and sends the FIRs to the State Crime Records Bureaus, who send this data to the National Crime Records Bureau. As one of the authors, Dr Soumitra Pathare, described in his recent book, Life Interrupted: Understanding India's Suicide Crisis, what we record as suicide "…ultimately boils down to what the constable at the local police station will record as suicide."

As one might expect, the decision-making process involved in recording (or not recording) a suicide is subject to the influences of social stigmas and fears around the phenomenon. Families will not divulge all the details surrounding the suicide of a loved one due to stigma and shame, or the misconception that suicide is still punishable by the law. In some cases, an individual is not eligible for life insurance if they die by suicide; or the circumstances of the death are not flagged as unnatural and missed entirely. One example is death by poisoning: although this is the second most common method of completing suicide in India (1 in 4 suicides), it may not be recorded as a suicide due to a lack of clarity around whether the person consumed the poison accidentally or intentionally.

Whereas at the scale of a single village, district or state, a few incorrectly recorded deaths may not seem impactful, research has estimated male suicides in India to be underreported by 27%, and female suicides by as much as 50%.

Suicides among women, in particular, tend to go unrecorded for a few reasons.

Firstly, the husband and in-laws of a woman who has died by suicide can be penalised under the Dowry Act, which may motivate the family to withhold information surrounding the death. Secondly, women (more than men) tend to turn to poison to attempt suicide, and as mentioned above, this method is highly prone to misclassification. Unlike hanging, for example, it is easier for the consumption of poison to be recorded as an accidental death (assuming the woman has consumed it thinking it is a medicine; “cough syrup” is a common misdirection).

The discrepancies add up significantly. In the ten-year period of 2005 to 2015, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study estimated 8,02,684 additional total deaths by suicide in India when compared to NCRB figures. In 2016 alone, the GBD estimate was 75% higher than the NCRB tally (2,30,000 via GBD compared to 1,31,008 via NCRB). When applied to 2021 data, these figures suggest 338 unrecorded suicide deaths per day in India in 2021.

The devil's in the data

To make matters worse, there is further missing an array of details and information needed to correctly understand and appropriately respond to suicide. (The first step in developing suicide prevention programs, after all, is understanding the nuances of the problem.)

The first and arguably most damaging of these is the lack of data on attempted suicide in India. Nationally, we do not collect information on attempted suicide -- this data is not recorded anywhere or officially collated by any national body (not by the police or health system). This is particularly important as individuals who have previously attempted suicide are at the highest risk of dying by suicide in the immediate future. Thus this group by themselves require proactive support; however, without knowledge as to who is attempting suicide, and where and why these are happening, little can be done in the way of prevention or responsive interventions.

Additionally, the NCRB does not publish any primary data on suicides and so researchers cannot analyse the data beyond what has already been analysed and presented. This limits our understanding because we cannot see the individual data points that may have been misclassified.

As pointed out by P. Sainath in his analysis of District Crime Records Bureau data in Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh in 2001, 82% of all suicides in that district had been classified as belonging to the "Others" column ("Others" being a reason for suicide outside of the existing categories such as family problems, illness, etc.). Within the "Others" column, many were described as cases where the person died of sickness due to an "unbearable stomach ache" which had occurred -- not coincidentally -- because they had consumed pesticide. Uncovering this revealed a much higher rate of suicide by pesticide poisoning than what was presented in the NCRB data.

Similarly, women are often not legally recognised as farmers unless they have their name on the patta (title deed), and so their suicides are recorded in the category of “housewives.” However, a farmer and a housewife will face a host of different socioeconomic difficulties which are contributing to their suicide; without accurate knowledge of who is completing suicide, there is little we can do to develop a solution.

To heap insult on injury, the NCRB’s annual Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India (ADSI) reports not only misclassify deaths by suicide but sometimes report conflicting numbers. ADSI 2021 published two different suicide rates for Chhattisgarh in consecutive graphics on state-wise suicide rates (Figure 1 & 2, below).

Combined, the resulting picture is unclear: who is most vulnerable, and why? In what direction are suicide rates shifting? Misled policymakers, health professionals, and researchers are prone to inefficiently prioritise funds and resources accordingly, an error we as a country cannot afford in our response to suicide.

A brighter, clearer future

While the journey to accurate data seems long and not without speed bumps, there are tried and tested methods that could drastically improve how and what data we collect, classify and have access to.

First, the responsibility of responding to suicide should fall within the purview of the public health system, not exclusively the police. Second, a mandatory psychological autopsy for each suicide (carried out as per standardised protocols) to determine the cause and surrounding details should be enforced. Finally, evidence-based surveillance systems (similar to disease monitoring systems in other countries) which collect data on attempted suicide and suicide at the community level can be implemented and scaled up.

Although the newly published National Suicide Prevention Strategy (NSPS) does set out to strengthen the existing data collection system, the "hows" are yet to be seen. It includes the promise of collecting data on self-harm and attempted suicide, developing a Management and Information System (MIS) for Mental Health which will be incorporated into the existing Health MIS, and expanding the number of columns under which data is categorised (thereby reducing the frequency of suicides disappearing into the data void of the "Others" column). However, there is not yet a mention of shifting the responsibility of data collection from the police to the public health system; a sorely needed institutional transition without which deep-rooted change is difficult to imagine.

For anyone who worries about the burden or costs of newer data collection processes on the health system, all we can do is point towards the existing burden of suicide as a leading cause of lost life in India. Surely, anything that helps us save lakhs of lives will ultimately benefit us all.

Sonali Kumar is a Research Associate; and Soumitra Pathare is the Director; at Centre for Mental Health Law & Policy, Indian Law Society, Pune.